Ancestors' Tales: retrieving memory from the landscape through oral storytelling

Presentation to a conference of the Tyne-Forth Prehistory Forum, Royal Society of Edinburgh, 29th September 2012

“... narrative is present in every age, in every place, in every society; it begins with the very history of mankind and there nowhere is or has been a people without narrative..: it is simply there, like life itself”

Roland Barthes

I’m going to be talking about narrative and storytelling – specifically oral storytelling – as a way of bringing the past to life. Underlying the presentation are two main ideas. First, that the creative techniques used by storytellers can be useful to specialist investigators of landscape, both when they’re developing research frameworks and when they’re trying to make sense of the evidence gathered in fieldwork. By ‘specialist investigators’ I mean prehistorians, archaeologists, environmental scientists and the like. Second, that the art of telling a good story is a means of compellingly conveying, to a wider audience, the ideas, thoughts and understandings that specialist landscape investigators construct about the evidence they gather. By ‘wider audience’ I mean other specialists, the general public, partner organisations, funding bodies and such like.

For those who have not experienced oral storytelling, it’s essentially someone telling stories to an audience, face-to-face, extemporary or from memory but not read from the page or from notes. Storytelling performances can take place in indoor or outdoor settings, and are for adults not simply for children. Audiences may vary from just a few people to a few hundred people. Storytellers themselves are many and varied and perform a wide range of material, from traditional folk tales, myths and legends to stories about environmental issues, about historical events or about archaeological sites and finds.

So, who are these ‘ancestors’, and in what sense, if any, are they ours?

The anatomy of connection

Adrian Targett and an ancestor © Bryan Sykes, Blood of the Isles

This is Adrian Targett, a school teacher from Somerset, with one of his ancestors, 'Cheddar Man' - whose skeleton was excavated from a cave in Cheddar Gorge in 1903 and later carbon-dated to around 7000 BC. When DNA tested in 1996 and 1997, 'Cheddar Man' and Adrian Targett were found to be related - a family connection across 9000 years. But demonstrating deep genetic connection doesn't, on its own, engender empathy. What makes 'us', today, interested in 'them', in the past? Why do we care about what happened to them? Why do we spend so much of our lives delving into theirs? A structural model I find useful to articulate linkage with the past is a three-part 'anatomy of connection' comprising people, place and purpose.

First: people links. Emerging evidence from genetic testing indicates most of us carry some DNA inside us that dates back to the hunter-gathers who colonised northern Europe at the end of the last ice age; and that those who arrived then have been persistent in remaining. We also have our own family ancestry to root us in the recent and sometimes quite distant past. And, as individuals, we may have experienced something which has given us a personal connection, physical, psychological or emotional, with a past event.

Second: place links. Some ancient names for rivers, hills, valleys and other places have survived from prehistoric times: distant echoes of voices from the past; a kind of embedded memory. Then we have actual archaeological finds and artefacts, together with ancient sites and historical monuments, to give us tangible connection with the people who made them and which we can encounter or visit in the landscape today. You don’t have to be a card-carrying archaeological phenomenologist to be able to experience a ‘sense of place’, investigate the significance of a particular site in its landscape setting, or think about who lived there, what they got up to, or what their hopes and fears were.

Third: links of purpose, intention and motivation. As a species, we human beings seem to find our origins and our changing cognitive and societal evolution over time to be inherently interesting. Furthermore, we seem to be intrigued by those prehistoric peoples whose remains and activities we study because, while they were physically and anatomically the same as us, they experienced life and made sense of their world in very different ways to us. And, I would suggest, culturally and philosophically we find insight about past changes (environmental as well as cognitive and societal) to be useful for managing our lives in the present and for planning our trajectory into the future.

Ancestral manoeuvres in the dark

But they’re an elusive lot, these ‘ancestors’; and tracking signs of their activity and shedding light on their behaviour, thinking and beliefs is both an intellectual and practical challenge for us.

“The remains of antiquity ... bind us more firmly to our native lands; hills and vales, fields and meadows, become connected with us, in a more intimate degree; for by the barrows, which rise on their surface, and the antiquities, which they have preserved for centuries in their bosom, they constantly recall to our recollection that our forefathers lived in this country”

This quote is something the Danish archaeologist and historian Jens Worsaae wrote in 1849, around the time the concept of ‘prehistory’ was being invented. Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology had been published between 1830 and 1833, Charles Darwin’s Origin of the Species was published in 1859 and John Lubbock’s Pre-historic Times in 1865. Ideas about the deep past were changing. If you excuse the flowery style, the slightly nationalist undertones and the gender bias, the quote expresses quite well the sense of rootedness and belonging that can link people today, in whatever place they live, with the evidence of the past that lies all around them.

The Eildon Hills © Visit Scotland

People today differ widely in their responses to traces of the deep past. Some are completely indifferent. Others stress the oddity of past ways of doing things and of being. To some the past truly is “a foreign country”: to others the past still lives around them. Assuming, like me, you’re interested in discovering things about the lives and behaviours of people in the past, here’s a selection of broad questions about our ancestors that I think prehistoric archaeologists and performance storytellers are both interested in exploring.

- Where did they come from and when?

- How did they survive and thrive?

- What did they think and believe?

- Why did they change over time?

- Who were they?

A good story helps to convey the facts

© Paul Frodsham, In the Valley of the Sacred Mountain, 2006

Archaeologists’ narratives are about the ancestors’ material culture and inferred behaviour. They discern broad ‘ages’ or ‘phases’ within which to explore specialist interests, tracking changes in culture and behaviour over time. They depend on applying analytical methods and scientific techniques to available evidence to gain credibility and authenticity. But a good story always helps to convey the facts.

Archaeologists operate within a framework of conceptual narratives. These include wider cultural constructs, theories and ideas about archaeological knowledge, and agreed methods of best investigative practice. They write specialist narratives about their areas of interest. And they can tell good stories about how they made particular discoveries, especially after a few pints of beer. However, archaeologists have varying relationships with ‘story’.

Individual archaeologists take different stances. Some have experimented with putting imagined ‘fictional’ scenarios into written works, some present and narrate TV programmes; some have even experimented with oral storytelling. Artists and illustrators are used by archaeologists to help with landscape representation and interpretation, putting visual flesh on the archaeological and environmental bones. But, with a few notable exceptions, there seems to be a lack of awareness within the archaeological profession of the potential benefits from engaging with professional storytellers or creative writers on archaeological projects; even a professional reluctance to do so.

I can illustrate this reluctance by quoting Bruce Trigger. In his book A History of Archaeological Thought (2nd edition, 2006, p.518), he comments that “Unsubstantiated speculation currently threatens to return archaeological interpretation to the highly subjective and irresponsible state of “story-telling” from which Lewis Binford and David Clarke, each in his own way, sought to rescue it in the 1960s.” While this remark is primarily a criticism of archaeologists who stray too far from hard evidence, it also speaks of a professional view prejudiced against what others would call ‘blue-sky’ thinking, or thinking ‘outside the box’ – the sort of conceptual gymnastics or thought experimentation that any scientific or social scientific pursuit engages in.

The facts help to create a good story

Storytellers’ narratives are about the ancestors’ imagined adventures and exploits. They select and recount particular moments where something unusual, unexpected or extraordinary happens to someone, somewhere. They draw on archaeological evidence about material culture and behaviour to give invented scenarios credibility and authenticity. In my view, in the field of historical and archaeological storytelling at least, the facts always help to create a good story.

We’ve all heard the saying “never let the facts get in the way of a good story”. It’s a glib and somewhat cynical view of storytelling in general; though arguably appropriate to a lot of what I would call ‘instrumental’ storytelling – that is, the narratives of advertising, marketing, corporate compliance and political propaganda. I contend that good oral storytelling both relies on and values authenticity (in the tale itself and from the teller) to enable the storyteller fully to inhabit the story, build up empathetic connection with an audience, and to help that audience remember and retell the story when they resurface in the ‘real’ world. Getting the facts right is crucial to the integrity of a story and to the credibility with which a teller is regarded.

In fact, the present-day storyteller’s concern with credibility and authenticity has considerable professional depth, traceable back at least to early medieval times; and, glimpsed through the eyes of classical authors, back into prehistory. Then, the role of the storyteller in serving the community (and distinct from the storyteller’s or bard’s role as eulogist for high-status individuals) seems to have been to function as the guardian of tradition, the conveyor of collective wisdom, the pathfinder and director of the way through story.

© B. Haggarty & A. Brockbank, Mezolith, 2010

Apart from its continuance in a few areas and in a few communities, this deep and multi-faceted oral storytelling tradition had all but died out in the UK by the 20th century. But oral storytelling was revived as an ‘alternative’ folk phenomenon during the 1960s, then re-invigorated as a form of performance art during the 1980s. Contemporary oral storytelling exhibits a broad spectrum of folk practice and performance art activity, and seems to be thriving throughout the UK. In the popular mind at least, oral storytelling is often perceived simply as making things up that aren’t true, or as something only for children, to keep them amused and entertained. And sometimes it is; though even as pure folk entertainment, the artistic integrity of storytelling will still depend on eliciting psychological, mythopoeic or emotional resonance for its underlying empathetic authenticity.

But oral storytelling is also a way of addressing serious issues like ecological crisis and inter-community conflict, and a means for supporting interesting work in areas such as organisational improvement and community building. Today, oral storytelling, and the imaginative visualising, thinking-on-your-feet and inter-personal communication skills it involves, are being applied in such varied fields as primary and secondary education, further and higher education, corporate training, trauma and grief counselling, personal development and heritage interpretation. In the latter context, storytelling in the landscape, on-site at historically or archaeologically significant locations - from barrows to battlefields and from homesteads to hillforts - can be particularly effective in bringing these locations to life, populating them with imagined but authentically created people, and giving new breath to vanished voices from the past.

From this, albeit highly compressed comparison between archaeologists’ and storytellers’ narrative approaches, I would argue that they complement one another.

Place narrative projects

This brings us to look at the ways in which oral performance storytelling, and the creative thinking and narrative development skills that it involves, can be and have been practically applied. Broadly, these applications relate to elucidating and celebrating a ‘sense of place’ and exploring connections in specific places between the past and the present. I shall illustrate something of the processes involved by briefly mentioning six projects I know something about, some of which I’ve worked on.

© Mendip Hills AONB

‘Echoes in the land’ involved professional storyteller Jane Flood working in nine Mendip villages as storyteller in residence for the Mendip Hills AONB, to recreate a new story for each village. The project culminated in a performance in Cheddar Caves, where some stories were told in the local dialect. In part a community-building project, it also promoted greater awareness within the contemporary community of the deep and recent history of the Mendips, helping to foster a new engagement with the landscape and its embedded memories. It involved Jane Flood in a lot of listening, mining memory from community members and from the landscape, then acting as imaginative midwife to give the stories new life and contemporary currency within the community.

‘Earthy Strong’ is a one-man show I perform which comprises historically-based stories and songs set in two particular areas – the Anglo-Scottish borders and the Anglo-Welsh marches – where I have personal, ancestral connections. The material covers the period from about 1600 AD to about 500 AD and involves the audience journeying back through time as well as between locations. The show explores the characteristics of border regions through the Middle Ages and unearths links between folk tradition, history and archaeology in those places.

‘Forgotten Lives’ was a show devised by Fire Springs storytellers, specially commissioned for the Independent Bath Literature Festival 2012, to celebrate the lives and achievements of a selection of Bath’s forgotten and half-remembered denizens. Performed by four storytellers as a set of first-person narratives it took the audience on a trip back through time, from around 1800 AD to about 800 BC. It also posed questions about memory and forgetting in history and legend.

The ‘Bath City Identity Project’ is aiming to create a new narrative for the city of Bath – a UNESCO World Heritage Site and home to some 80,000 people. The project’s core idea is to devise a clear, overarching story to tell about Bath’s uniqueness as a place, for its residents, visitors and the wider world; a story that will celebrate substantive but lesser-known aspects of the city’s present character, its history and prehistory (not just its over-exposed Roman and Georgian heritage) and that will include stories that have not yet adequately been told. Essentially a city-wide community-building project, it is not a branding exercise but a genuine experiment in civic inclusivity, creativity and authenticity.

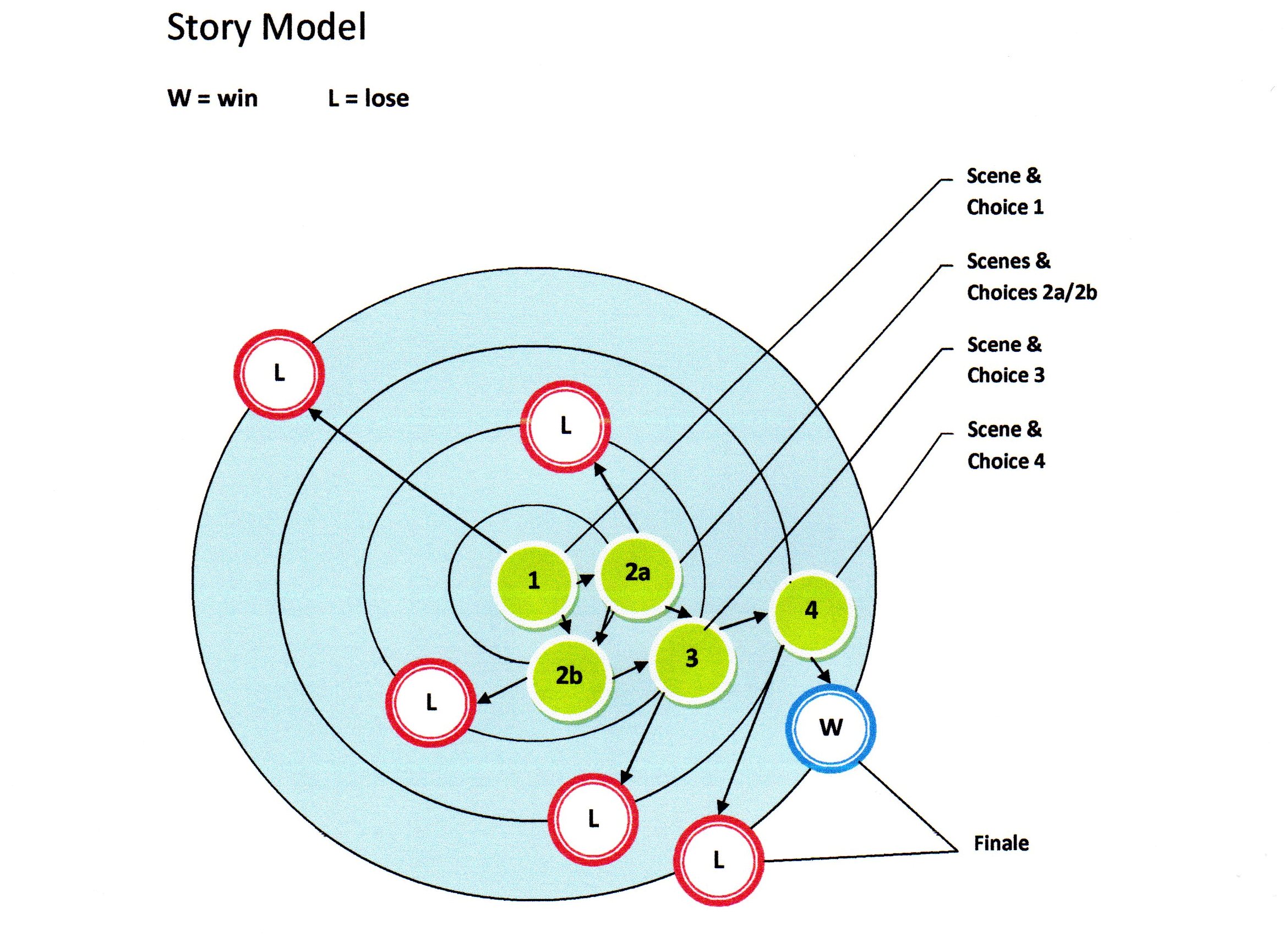

'Ghosts in the Garden, Schematic Story Model

'Ghosts in the Garden’ is a project specific to a particular place and time: Sydney Gardens in Bath around the period 1800 – 1830. Part game, part story, part immersive soundscape, present-day visitors meet and interact with Georgian ‘ghosts’, drawn from all social classes and modelled as far as possible upon historically researched ‘real’ characters. As a visitor experience the project aims to reunite the physical space of the modern park with its own past as a pleasure garden and with the present Holburne museum, the gardens’ former entry-point, tearoom and hotel. The project uses pre-recorded stories and GPS technology to bring the gardens alive, while also subtlely conveying, within the stories, information about the history and landscape archaeology of the site.

Last but not least, because it’s a really interesting project taking place in the Tyne-Forth region, ‘Talking Bones’ aims to bring alive the archaeology of selected places in Northumberland by telling the stories that emerge from them. The first phase of the project has involved collaboration between archaeologists (Paul Frodsham and Harry Beamish) and storytellers (Malcolm Green and his colleagues from A Bit Crack storytellers) with each performing their stories to community audiences, as scientific fact and as imagined fiction respectively. Those involved in the project now hope to embark on a series of walks, to elicit further stories from specific ‘song lines’ in the landscape.

I hope the example of these six projects has shown that narrative approaches and techniques can be successfully applied in a number of diverse contexts to do with ‘place’. Of those in which I’ve been involved, my participation has varied from performing stories to facilitating workshops in creative thinking and narrative development. From this involvement, and from knowledge of other projects like them, I have learned that there is no template methodology or set of techniques that are commonly applicable. Each project demands and requires a bespoke response. But from storytelling production to heritage interpretation and from small-scale to large-scale community building, some key working principles are apparent to me: respect complexity but seek simplicity; all voices have equal right to be heard; listen and stories will emerge.

To complete this part of the talk, this diagram summarises the inter-active relationships between landscape specialists, storytellers and the wider community and how they interrelate. For example: the community shares information and discoveries with specialists, and shares stories with and supports the livelihood of storytellers; specialists make discoveries and share their knowledge with the community, inform the storytellers’ craft and use storytelling expertise; and storytellers support specialist interpretations of the landscape and convey meaning and sense-making to the community.

Voices of the Votadini

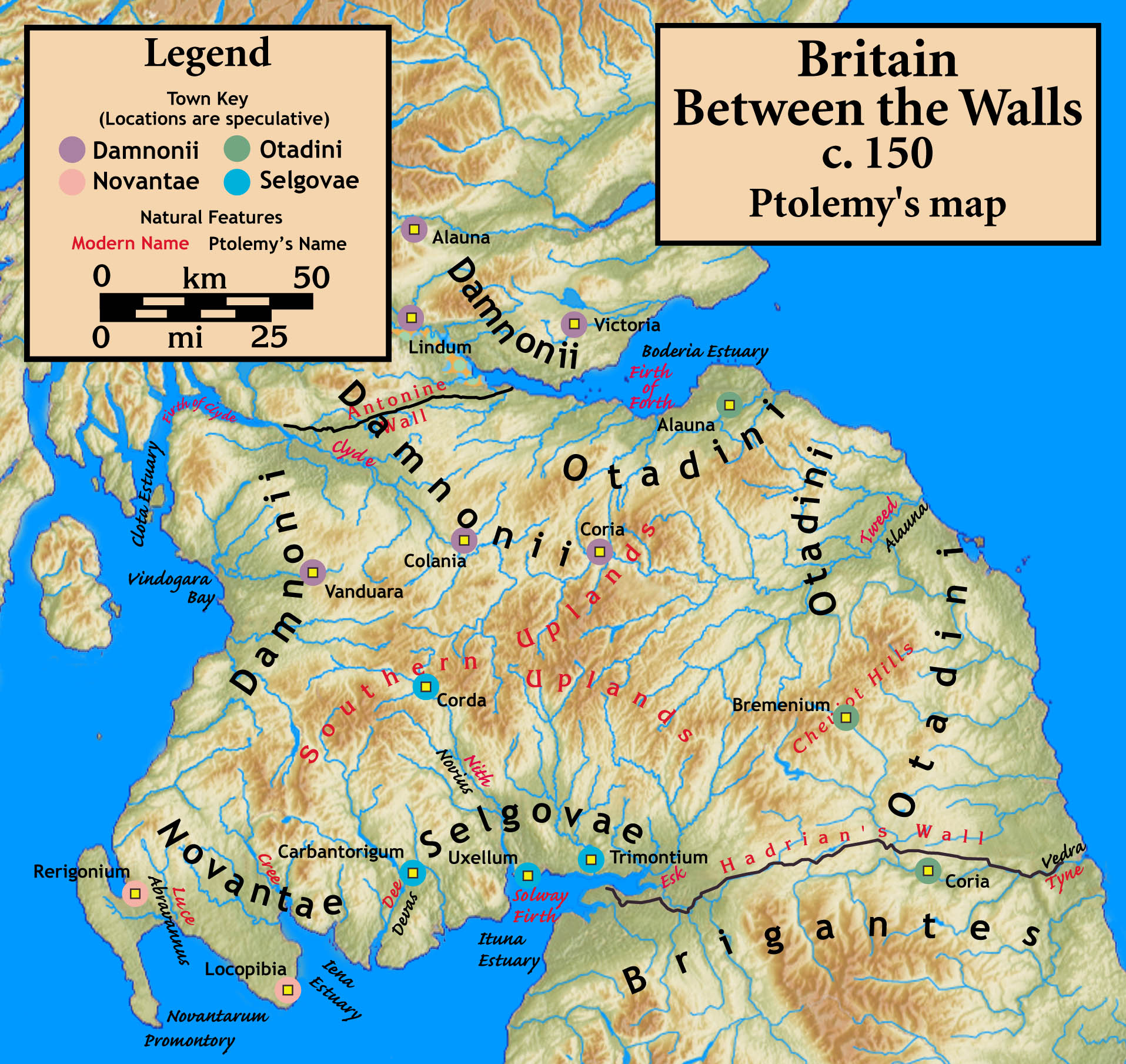

In this final section of the talk I’ll touch on how one might approach the development of a place narrative for the Tyne-Forth region. Then I’ll illustrate how to put some flesh on one or two of the bare bones. What stories might the Votadini have told each other about their ancestral past, I wonder?

©Wikipedia

Three vital ingredients for story-making are theme, character and location. Under these headings I’ve listed a few items just to illustrate the narrative possibilities – which for the Tyne-Forth region throughout prehistory are considerable. I’m sure you can all think of many more suggestions under each of these headings, from your own specialist knowledge and interest.

Themes Flooding of the North Sea basin Worsening climate causing hardship Infectious disease causing death Conflict (inter-tribal, Roman invasion) Trade and inter-community contact | Locations Whin Sill axe factory (Group XVIII) Uplands, valleys, coastal plain, coast Particular wild places (hilltops, forests) Specific domestic places (hut, village, fields) Specific sacred places (tombs, springs) | Characters Hunter-gatherers, hunter-gardeners First farmers and herders Chieftains and warriors Bards and healers Metalworkers |

The processes of story-making and story-telling are huge topics in their own right, which I’m not going into in any detail here. There are many concepts and tools which people study to degree level. But I would like to make a few key points here. First, in creating any story, the storyteller needs to imagine as much relevant descriptive detail as possible, in order to ‘picture the scene’ in his/her/their mind. When telling the story, the storyteller won’t need to recount all this detail, otherwise dramatic momentum risks being lost – but the storyteller will describe selected detail in particular scenes as well as moving the action of the story along. Second, there are a number of basic story structures to provide a framework for whole stories or scenes within a story. These include: beginning/middle/end; set-up/complication/resolution; and separation/initiation/return. Third, there are several basic plot scenarios, onto which can be grafted any number of individual narratives. For example: the voyage and return; the quest; rags to riches. Once you’re familiar with basic story structures and plot scenarios, you can spot them being played out in most narrative fiction and Hollywood movies.

Now let’s look at three possible stories for our Votadini ‘ancestors’.

The healer’s tale

First: the healer’s tale – a close call in the wild, sometime around 7000 BC. I’ve set out a few suggested ‘bones’ for a possible story. A woman hunter-healer goes out to gather honey and herbs with healing properties, and to trap small animals with curative attributes. She has to be alone, for ritual purposes. After collecting honey, she encounters a wild pig which attacks her. She fights and kills it, but is wounded. She treats herself, but falls unconscious. She has a dream or trance. She wakes, transformed by her experience and the dream. She returns home safely. Home could be the Howick site, or somewhere similar.

Mesolithic rock painting from Spain © M. Ehrenburg, Women in Prehistory, 1989

I’m not concerned here with the bones of the story but with the questions the storyteller asks when creating it. Questions like:

• What’s she wearing and carrying – clothing, adornment, tools, protection?

• What does her family comprise – living and dead members?

• Where does she live and what does her home look like?

• What’s the landscape like – trees, plants, views?

• What are her thoughts and inner feelings?

• What does she hope for and fear?

• What can she smell and hear?

Some of these questions we can answer, in whole or in part, from archaeological evidence: some we can’t. But to create a good story, the storyteller needs to fill in at least some of the gaps, to activate, guide and satisfy the listeners’ imagination. So the storyteller needs to ask creative questions. And some of these questions are similar or complementary to those a landscape specialist might ask from a research perspective. How could we discern a healer in the archaeological record? What chemical sampling techniques exist and could be applied in particular locations (e.g. hut floors) to give us better diagnostic capability about domestic activities? How can we estimate the size of a Mesolithic household/family group? Imagining this woman’s story in the distant but accessible past helps us to ask questions about what sort of archaeological traces we might proactively look for rather than just passively find.

The farmer’s tale

© Cornwall Heritage Trust

Second: the farmer’s tale – a story of life and death in the uplands, sometime around 1500 BC. A farmer is out in the fields around his village, tending stock, while his wife is waiting to give birth. But the wait ends in death, for mother and child. The bodies are prepared, cremated and the remains interred in a nearby ancient cairn. Again, I’m not concerned here with the structure of this possible narrative, but the sort of questions that an oral storyteller would need to ask to create and perform a credible tale around such an occurrence; and how these questions might potentially inform an archaeological research agenda. Questions like:

• What is the hut like inside and how is the interior arranged into separate compartments?

• Where did people give birth and how were the bodies of the dead prepared?

• What crops are growing and animals pastured in the fields?

• What are the birth customs/rituals/taboos?

• What are the death rituals/taboos?

Again, some of these questions we can answer, in whole or in part, from existing archaeological evidence: some we can’t. But we can conduct thought experiments and ask further questions. What sort of research framework could we design to estimate infant mortality in the second millennium BC? What excavation and chemical sampling of field systems might we carry out to yield data on animal husbandry and crop rotation? How do we develop the archaeology of kinship? As new scientific techniques become available to archaeologists from other disciplines, we may be able to investigate such questions more easily; but if we ask imaginative questions first, we may also be able to devise new scientific techniques and archaeological sampling methods to proactively address them.

The warrior’s tale

© Wikispaces

Third: the warrior’s tale – death in the afternoon in the Tweed Valley, around 80 AD. Native warriors prepare and execute an ambush of Roman soldiers. They kill some of the invaders, but are left with a sense of foreboding about the future. In creating a story around an episode like this a storyteller would ask such questions as:

• What arms and armour are natives and Romans using?

• What tactics are being used on each side, and why?

• Who is mounted (in chariots?), who on foot?

• What rituals or taboos surround warfare?

• Who will miss them if they don’t return?

• What motivates or compels them?

Again, what’s of interest to me in this example is the complementary nature of the research questions arising from ‘creative artistic’ and ‘analytical scientific’ perspectives. How might we look for the outcome of such an encounter through battlefield archaeology or field-walking? How can we devise means of scientific evaluation to discern whether certain finds of Roman material in late Iron Age contexts are the result of trade or the spoils of war, instead of falling back on opinionated intellectual disputation? How do we apply the techniques of modern conflict archaeology to prehistory?

What I think particularly important from these three brief illustrations is to highlight the cognitive process involved. Rather than just thinking about things from a find-based or site-based perspective, that is through the accidental incidence of archaeology, it is also essential (though challenging) to think about things from a prehistoric person perspective – from what we might term as the ‘agency of the ancestor’.

Imagining people in their place and time

The landscapes which successive prehistoric people inherited, inhabited or otherwise occupied contained the remains and visible traces of previous people’s lives – track-ways, way-markers, tombs, community assembly places, rock art, encampments, settlements, field systems, territorial markers and boundaries. And if people didn’t know directly or indirectly who had made these things or what they were for, they would have made up stories about them. Apart from tantalising and problematic traces of some of these stories embedded in folklore and legend, we don’t know what narratives successive prehistoric communities told themselves about the land they lived in, or about the people who had lived there before them. Nor do we know directly what prehistoric people really thought about their world, how they experienced it, nor how they understood it to be.

© Aaron Watson, British Archaeology, September/October 2012, p.21

In the absence of direct oral or written evidence from the prehistoric past we make up our own narratives for our ancestors, based on what we infer and imagine about their lives from the sites and finds they have accidentally bequeathed to us. These narratives range from specialist narratives constructed by archaeologists and prehistorians that focus primarily on documenting material culture, to fictive narratives constructed by creative writers and storytellers that attempt to reconstruct daily lives, experiences and adventures, as well as hybrid narratives in between these extremes. But it seems to me that from specialist monographs to general interest books, from text books to graphic novels, what all have in common is the desire to inform and extend our imagination about what life was like for them, in their place and time.

For me, oral storytelling is a particularly powerful tool for pursuing this work of the imagination. It involves direct, face-to-face, inter-personal engagement between storyteller and audience which leads to states of heightened awareness in the moment, conducive to subtle and sensitive transmission of thoughts, feelings and information. It is a flexible means of handling factual and fictional information together which, when done well, enables complex information to be conveyed clearly within a relatively simple dramatic framework, and where story elements can be changed as new evidence emerges or to satisfy different audiences. And it is wonderfully and sustainably portable, suitable for lecture theatre or drama theatre and fireside or mountainside, and leaving no trace behind except in someone’s mind.

Investigating people from our place and time

It seems to me that a useful approach to investigating our ancestors’ lives from our place and time is to focus on asking interesting questions of the evidence they have left us, not to focus on trying to come up with speculative or premature answers where the evidence is thin or non-existent. The approach I’m interested to practise would promote the use of thought experiments; in generating different scenarios that accord with the evidence, in exploring these scenarios, and in seeking to devise ways of obtaining further evidence to evaluate these scenarios. It involves thinking through the evidence of artefacts and sites, not just thinking about them.

Green Knowe hut platform © David Metcalfe & George Jobey

For example, looking at the unenclosed platform settlement of Green Knowe in Peeblesshire (first excavated by Dick Feachem in 1961, then by George Jobey in 1977 and 1978, and on which I worked as a post-graduate student), it is possible to generate a number of different scenarios for the occupation of the site on the basis of the archaeological evidence found at that time, and clearly and circumspectly concluded on in the excavation report (Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 110, 1978-80, pp72-113). For example: as either a single, relatively short-lived settlement or a long-inhabited one; as a year-round permanent location or a seasonal occupation site; as a small, localised, self-sufficient family group or a component of a regional web of inter-connected communities. Designing ways to test the likelihood of different scenarios such as these might usefully inform the design of further excavation projects at similar sites elsewhere.

Given the immensely varied quality and quantity of the evidence available to us, investigating prehistoric people from our place and time obviously means accepting uncertainty, accepting that there are limitations to intelligent speculation about past human activity, behaviour and belief. But I believe we also need to embrace creative ways of problem-solving and imaginative ways of communicating specialist findings and conclusions. If the challenge is that of multi-variate, multi-linear complexity, then the response should be multi-disciplinary, multi-vocal conversation.

Against this background and in this context, I believe that the creative methods used by storytellers can help landscape specialists to ask interesting questions for research purposes, as well as help them tell good stories about what they find and how they found it. I’m not saying that landscape specialists don’t already engage in creative or imaginative thinking. I know they do. I’m suggesting that more purposeful collaboration between landscape specialists and storytellers would be interesting and rewarding for all concerned.

It’ll come

The qualities George Jobey exhibited included imaginative thinking, wide-ranging interests and respect for the evidence – pushing it as far as he could, but never too far. The methods he employed included taking a whole-landscape approach, conducting methodical fieldwork and ensuring prompt publication of his survey and excavation activity. The big thing I learned from George Jobey is that it’s all out there waiting for us. We just need to look at it the right way, from the right angle and in the right light.

Thank you.

| |